Dragons, tigers, one bear

Sunday | October 3, 2010 open printable version

open printable version

Sawako Decides.

DB here:

As has become our habit, we’re at the Vancouver International Film Festival, gulping down movies. The perennial Dragons and Tigers collection of recent Asian film is especially ripe this year, at over forty-three features and many shorts, and of course there are several other choices, across ten venues, competing for your eyeballs. Herewith, my first dispatch from this sunny, hospitable city. Kristin will follow up soon.

A girl, a boy, and many guns

She’s completely ordinary, “below-middle,” as she proclaims. Her contribution to a conversation is always a couple of steps behind. She spends her nights watching TV and guzzling beer. She has lost five jobs and been dumped by five boyfriends. Her main relaxation seems to be colonic irrigation. But when she’s fired and her father lies dying, she returns to her hometown to take over his clam-processing factory. She brings in tow her latest paramour, a twitchy ex-toy-designer who enjoys knitting.

Such is Sawako, who has the face of an anime princess and the mind of . . . well, that’s part of the problem. Psychologically, she’s the opposite of those fast-comeback youngsters spraying American indies with quirk. She mopes in her father’s factory, absently minds her boyfriend’s daughter, shrugs off the malice of her former teen friend, and ignores gossip about why she left town in the first place. Nothing can shake her obdurate passivity. She won’t fight. With beer as her only solace, Sawako seems not the stuff of drama at all.

But drama, tradition tells us, pivots on decisions (usually bad ones). Sawako Decides surrounds a woman resigned to misfortune with a range of eccentrics who do take action, sometimes recklessly. There are the older women who work in the processing plant, the faithless boyfriend with his powder-blue sweaters, the vindictive ex-friend, the alcoholic father who rips off his IV for a fight, even a college girl doing research on toxic clams. When Sawako finally chooses to do something, she’s acting, she says, for all the “below-middle” people—that is, nearly all of us. Associated throughout with body wastes, she turns the tide: Even the feces she spreads on the family garden yield a giant watermelon. The film ends with a trim long take in which Sawako finally blows her top and finds an agreeably aggressive use for her father’s bones. Ishii Yuya’s film shows how the blankest of characters can, if treated with wary respect, yield engaging cinema.

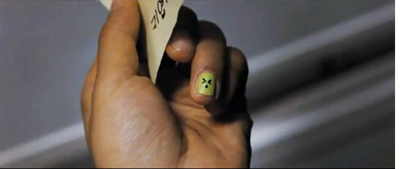

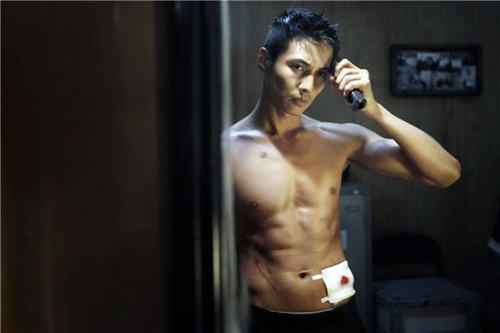

Won Bin is probably best known to Western audiences as the scatty, tormented son in Bong Joon-ho’s Mother, but he’s become a major Korean heartthrob. I know this because of the collective gasps and shrieks that greeted moments of The Man from Nowhere, a grisly action picture by Lee Jeong-Beom. Won plays a retired government agent running a pawnshop in a seedy neighborhood. He reenters the underworld to rescue a neighbor woman’s daughter, snatched by a drug gang for a little child labor and organ-stripping. He is a Bourne-style killing machine, and he is given plenty of chance for some rousing brawls and gunplay (though most of his fighting skills can be credited to editing and blur-o-vision camerawork). Mountainous, bug-eyed, and ominously silent bad guys round out the cast. Director Lee is also shrewd enough to feed the fanbase. There are some touching moments between the girl and the hitman; she even gives him a decorative fingernail while he sleeps. The film’s pin-up image shows Won, stripped to the waist at the mirror, clipping his hair, a bloodied groin-level bandage artfully completing the ensemble. (If you can’t wait, see the end of this entry.) A limited North American release comes later this month.

Excess, two varieties

I’ve written briefly about Sono Sion’s perverse coming-of-age tale Love Exposure, and this year’s Vancouver fest brings us his latest, Cold Fish. Who would have thought that business rivalry between two tropical-fish vendors would lead to the carnage we see here? Meek Shamoto has a sexy wife and a disobedient teenage daughter. An aggressively friendly rival, Murata, owns a much bigger shop and offers to take the wayward Mitsuko under his wing. Soon Murata reveals that he plunges as voraciously into murder as he does into fish connoisseurship, and Shamato is caught up in the untidy business of human butchery.

A charnel-house of copulation and dismemberment, the film takes place in a vacuum; a police investigation comes virtually as an afterthought. Cold Fish is more linear and genre-bound than Love Exposure, but when the quiet march of Mahler’s first symphony signals the onset of dread you recall the wilder side of the earlier movie. Also carrying over is the blasphemous use of Christian iconography, associated here with slaughter and child abuse. The film is in the tradition of The Family Game and other dismantlings of Japanese domesticity. Once again, you can find as much lust and murder as you like just by looking into the nuclear family. In this case, the choice offered to the father is straightforward: be a wimp or be a brute. Sono aims to outrage, but once you know that you’re in for a bloodbath, you settle comfortably in for an engrossing exercise in splatter, Japanese-style.

At the other extreme is The Drunkard, Freddy Wong’s adaptation of Liu Yichang’s well-regarded novel about a dissolute writer. Lau wants to be the Hemingway of Hong Kong, but his addiction to alcohol and his inability to love drive him into writing film scripts, pulp fiction, and eventually pornography. The fear of selling out your artistic ideals may not strike a chord in the age of Damien Hirst, but in the 1960s, the novel’s epoch, it held sway over literary culture. Lau’s struggle is presented as an oscillation between his collaboration on a literary magazine and his grubby business dealings with movie producers and publishers. In between, and constantly, he smokes and drinks. The women along his downward path include a seventeen-year-old temptress who has read Lolita, a sincere working woman who offers him lodging and sex, and an aged landlady who thinks he’s her son. His drunken refusal to sympathize with their needs brings sorrow to nearly all and death to a couple of them.

The Drunkard is shot in an unusual style. There are almost no long shots; the framing above is about as far back as the camera gets. Nearly everything happens in medium-shot and close-up. Wong was partly making a virtue of necessity, since streets and shops of the Hong Kong of the 1960s could not be reconstructed on the film’s budget. The positive result is an unrelenting concentration on Lau and repetitive bits of his behavior–gesturing with a cigarette, pouring whisky, or fading into a blackout. From scene to scene, we’re confined to his awareness, broken by fragmentary memories of wartime Japanese invasion. Only after his binges do we learn how viciously he acted when under the influence.

This tightly circumscribed world is enhanced by shots focusing on only a curtain edge or a streaked whisky glass, while people and surroundings drown in a blur. Shot on the Red camera, The Drunkard shows that high-definition digital is perfectly capable of giving foregrounds or backgrounds a hallucinatory softness. That softness, you could argue, is a correlative for the drunkard’s vision, locked on details and oblivious to the flux of human passions around him. In its effort to render the glowing warmth of alcohol, Wong and his cinematographer Henry Chung have given digital cinema a decisively subjective turn.

Two men and a sofa

Ho Wi Ding’s Pinoy Sunday is a heartfelt, low-pressure comedy-drama that makes some telling points about cultural dislocation. Dado and Manuel are Filipino “guest workers” in Taiwan. Friends since high school, they work in a bike factory and live in the factory dormitory. In their dreams they imagine installing a lavish raspberry-bright sofa on the dorm roof where they could lounge, drink beer, and look at the stars. One day, visiting Pinoy on break, they see that very sofa abandoned on the street.

Emigrant Filipino workers fill the lower-rank jobs in many Asian countries, and I’ve seldom seen fiction films show the texture of their lives. Through Dado’s phone conversations with his family, the pain of loss comes through. He buys his daughter a Barbie for her birthday, even while he carries on an affair with an émigré woman (who herself has a husband and family back home). Manuel is on the make, but with winning naivete has a knack for picking the wrong women to idealize (hookers, policewomen). In a way, the sofa becomes the tangible emblem of not just material comfort but the men’s aspiration for a more stable life.

With something of the wistful satire of 1960s Eastern European films like Intimate Lighting or The Fireman’s Ball, Pinoy Sunday turns an anecdote into a mini-saga. (It was inspired by Polanski’s Two Men and a Wardrobe.) At the canonical turning point (circa 28:00), Manuel persuades Dado to carry the sofa back to their dorm before the gates close. The ensuing misadventures recall Laurel and Hardy, but with stronger sentiment.

Their journey reminds them they are outsiders. A TV reporter thinks they’re Malaysian. Trying to explain an accident to a cop puts them at a disadvantage. Their inability to speak Mandarin gives us a crash course in how gestures, English phrases, and situational logic are pieced together to communicate across cultures. At the height of the men’s frustration, there is a poignant musical interlude that evokes magic realism, but that moment is immediately undercut by sober reality. Yet our concern for these two resilient strivers is rewarded with a sort of happy ending.

Finally, the bear of this entry’s title is Alex Law’s Echoes of the Rainbow, the Hong Kong film that won the Crystal Bear at this year’s Berlin festival. I haven’t seen it yet but I hope eventually to pass you some words about it.

The Man from Nowhere.